A short answer is that it was John Barrymore's former Manhattan apartment that playwright Paul Rudnick was shown (some online articles say that Rudnick lived there, but he doesn't make that assertion in his script notes.) This coincidence sparked the writing of the play.

But there are meaningful parallels between Barrymore and our protagonist as well. First, however, who was John Barrymore?

Perhaps even in 1991 it was too early to mention that John Barrymore is Drew Barrymore's grandfather. The first generation of Barrymore actors were Georgiana and Maurice Barrymore (Drew's great grandparents.) The next and most legendary generation was composed of the siblings Lionel, Ethel and John. They all are best known now for their movie performances, but they began on the stage.

Ethel was the first to become a star in 1901, in the unlikely Broadway show Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines by an early Broadway playwright I've been reading a lot about lately, Clyde Fitch (His play Her Own Way was the first ever done by Humboldt State, and is being restaged as a radio-style drama by HSU Theatre, Film & Dance on October 3 and 4.)

Captain Jinks was also John Barrymore's first Broadway appearance. As I Hate Hamlet says, he started with mostly light comedy, but he did try more serious drama before Hamlet, including a role in Ibsen's A Doll's House (again with sister Ethel) and more individually in an adaptation of a Tolstoy play,confusingly retitled Redemption (since that was the title of a different Tolstoy novel.) He also did an historical drama called The Jest with his brother Lionel--and this made Lionel a star.

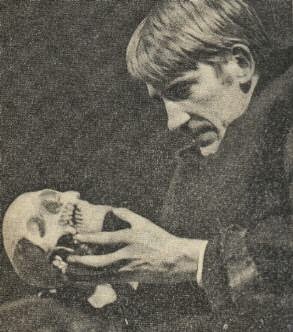

John Barrymore warmed up his Shakespeare with voice lessons and a reputedly very uneven Richard III. But then in 1922 came his triumphant Hamlet. His erratic behavior and lack of concentration and consistency were on hold for awhile. He prepared for Hamlet "meticulously," writes famed critic and theatre historian Brooks Atkinson. The result: "John Barrymore played a Hamlet that most people ranked with Edwin Booth's, by tradition considered the greatest."

Another critic wrote that Barrymore had revolutionized Shakespearian acting by ending the "school of recitation." Barrymore's performance was "alive with vitality and genius--a great, beautiful, rare Hamlet--understandable and coherent."

John Gielgud, whose own Hamlet would eventually break Barrymore's Broadway record for performances, saw the Barrymore performance and "admired it very much," noting that he had "a wonderful edge and a demonic sense of humour...Of all the actors in my time I felt he must be the nearest to Irving, with the same kind of extravagance and flowery, sinister power."

Barrymore's Hamlet is also notable for his interpretation of Hamlet's relationship with his mother as Oedipal. This Freudian approach was adopted wholesale by Olivier, especially in his movie version of Hamlet, which he directed. (Gielgud also mentions that Barrymore "cut the play outrageously" so he could extend the scene between Hamlet and his mother that exemplified this approach.)

A few years later Barrymore took his Hamlet to London, and triumphed again. He then gave up the Broadway stage, moved to Hollywood and made movies, where he fully earned his reputation for womanizing and especially for drinking (apparently emphasized more in the original I Hate Hamlet Broadway production than at NCRT.)

But it is not true, as stated in I Hate Hamlet, that he never returned to the stage. He made one last Broadway starring appearance. In a reputedly mediocre play (My Dear Children) he gave "a first-rate performance," Atkinson writes. "There was a kind of admirable, if perverse gallantry about this final fling at the stage..." (Atkinson saw this play himself, and may have seen Barrymore's Hamlet.) This play ran for four months in 1940. John Barrymore died in 1942.

So the parallels between Barrymore and Andrew Rally, both obvious and subtle, underlie this "boulevard comedy" as Rudnick describes it. Rally comes from commercial TV but at least part of him longs for artistic challenge and expression (so he auditioned five times for this Hamlet.) Barrymore came from commercial theatre and was uneducated and untrained for classical roles, yet he pursued such roles and worked hard to excel in them. Barrymore also knew the temptations of Hollywood--in his case, the movies.

They are both conflicted. And of course they are talking about the most famously conflicted character in classical drama: Hamlet.

The contrasts between Rally and Barrymore--notably involving women and drink--also figure in the comedy, but the relationship they build in the second act is based on these common threads, as well as one more: the brotherhood of Hamlets.

Playing Hamlet is a kind of rite of passage for actors (which is partly why there is a new Hamlet somewhere in England almost continuously.) Especially for a young actor it is the most complex role, offering the most challenge and the most breadth of opportunity for interpretation. (Lear is the equivalent for older actors.)

|

| David Warner Hamlet 1965 |

There is a kind of brotherhood established by the actors (a few of them women) who have played Hamlet, and a feeling established in theatre lore that after playing Hamlet an actor is never the same. You get some sense of this in the conversation that David Tennant has with other Hamlets like Jude Law and David Warner in the BBC's "Shakespeare Uncovered" series, which is viewable on YouTube. I remember Tennant talking about this brotherhood of Hamlets and the mystique of the role in an interview, which I can no longer find.

A personal note: I don't recall actually meeting Paul Rudnick when we were both writing for Esquire, but I heard about him from mutual friends and editors. The word was that he was very funny, and very New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment