[a slightly different--and of course longer-- version of my Journal column as it appeared this week...]

Last April,

Crawdaddy: A Freak Tragedy, produced by the Canadian mask and puppet group, the Calgary Animated Objects Society (CAOS) in conjunction with Dell’Arte and Four on the Floor Productions, came to the Arcata Playhouse for two weekends of workshop performances.

In the performances I saw of that show, Crawdaddy (played by James Griffiths of the San Francisco Mime Troupe) was a dominant and sometimes threatening personality, despite being barely ambulatory due to his grotesque crab tail and feet. His marriage with Veronica, the Fat Lady (Jacqueline Dandeneau) was interdependent with their attempts to take and then keep control of their freak show, which often involved murdering other freaks, including Crawdaddy’s father.

But there was surprising tenderness in their relationship, and in Veronica’s struggle to have children (stillborns that she justified keeping in jars as part of the show), and then in their family feeling when Veronica gave birth to Siamese twins, Lily (Esther Haddad) and Heather (Zuzka Sabata.) The two girls, writhing in each other’s permanent embrace, were lively and real, and of course part of the show, playing odd and haunting melodies on saxophone and violin.

Through dialogue and Crawdaddy’s monologues, and particularly the stories told by the vaguely sinister puppet, LV Willikers (the voice of David Ferney), more of the family drama was revealed, always returning to the particular culture of freaks in freak shows, as well as the permeable definitions yet ironclad realities of freakishness and normality. So when one of the girls fell in love with the dim but otherwise “normal” janitor, Val (Tyler Olsen), the mood alternated quickly between acceptance and menace.

The mood was captured by a story the puppet told with pride and nostalgia about his father’s job testing out the wringers of washing machines by getting wrung through them, and popping back to normal size afterwards. The assembly line as freak show suggested another riff on economic dependence at the edge of existence.

The essence of a freak show—of the need to satisfy the entertainment desires of normal folk with freakishness and freakish behavior—was a unifying theme, and just how this affected the family was often demonstrated in how many coins and bills showered the stage from the darkness around it. When survival was again threatened, Crawdaddy devised a one-time-only showstopper, the chainsaw separation of his daughters, which ended predictably in their deaths. In his last soliloquy, Crawdaddy refused to be judged, judging instead his audience and the darkness within human nature which he shared and reflected.

Together with the music and bizarre comedy, this was an edgy evening, and with themes shared with Shakespeare and especially Greek drama, it certainly was in the neighborhood of the tragedy in its title.

When this show returned to the Arcata Playhouse last weekend, it had a new director (Bob Rosen) and though it had many of the same elements and most of the same actors, it was vastly different. Crawdaddy (now played by Christopher Hunt) was at times vaguely threatening, but up and about on his not very freakish feet. Val was now a comical wannabe freak, and LV Willikers (with David Ferney clearly visible, part of what I presume was some often repeated, possibly postmodern joke about showing how the tricks are done) was now just a corny performer. His grotesque narration was gone.

The performances were still good, but gone also was much of the text and all but hints of the subtext. There was more music (by Tim Gray), fancier scenery and more stage tricks, which a woman seated behind me aptly but repeatedly called “clever.”

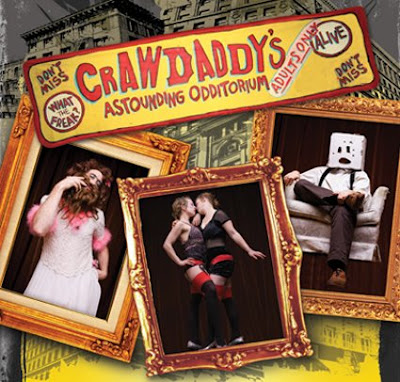

The show is now called

Crawdaddy’s Astounding Odditorium, and dropping the “tragedy” from the title is fully justified. The family history and drama, and particularly the drama of the freak show and its relationship to money and customers, is mostly gone. Though that’s suggested when one of the separated sisters survives but makes her ventilator part of the show, there is comparatively little emotional consequence to the separation, and the moment is without clear motive or outcome.

Some residual suggestions or fragmentary outlines of a story remain, but the storytelling is ineffective, lost in a furor of attempted effects, too many of which fell flat. The show now seems to want to be a kind of musical comedy, but it’s not that funny, and the music—while impressive, with some dazzling choral singing—just doesn’t have the wattage to carry a show.

Having dumped the tragedy and actual storytelling, it had nowhere to go but as a collection of sportive bits and tricks. Some work, but are they really worth it? It’s odd but not unprecedented to see a show in the process of development go backwards. I can’t totally dissociate what I saw this weekend from the show I saw last spring, but I experienced it as meandering, meaningless and soulless.

There was some criticism last spring over the whole issue of dramatizing a freak show, which might have been avoided had the historical context been made stronger: the program said the play took place in the 1930s but there wasn't much to support that on stage. Freak shows were common then, and still existed at least into the early 60s when I passed by their remnants at traveling carnivals.

The idea of focusing on the culture of the freak show performers--very strong in the first version, still present to a degree in the new version--remains a powerful idea, if used to explore issues such as what constitutes entertainment and what it requires of entertainers (are they all freaks to a degree?) and especially the relationship of money to this enforced identity. If my memory is accurate, there was a strong suggestion in the first version that Crawdaddy had been born into a freak show family but was normal at birth, and deliberately deformed. There was a story told of cruelity to get him to perform.

In any case, the new version treads towards treating freaks with the Barat sensibility--by overtly making fun of them it means you aren't really making fun of them, although everybody's laughing. It's a little uncomfortable without being edgy--and though the freaks are more cartoonish than freakish, it's still a question whether this is derisive. It's worth noting as well that much of the tradition of satire and clowning can be traced to the court jesters, and their origin in the "fools" who were kept as entertainment in homes of the rich as well as royal courts. Early on, these fools were mentally deranged or deficient and physically abnormal: they were freaks.

There's something else about the original Crawdaddy show that upset people. The first version was definitely darker, without any trace the of a happy ending. This disturbed some people, and it was meant to be disturbing--that's what gave dealing with these issues their edge. Could it be that a lighter tone was adopted to please audiences? For a century or more, the death of Lear and his daughter were considered too shocking for audiences, so Shakespeare's

King Lear was rewritten with a happy ending. More than the ending was changed in this show, and it wasn't Lear to begin with, although to my mind it had more potential than a lot of new shows I've seen. I hope this isn't why it was changed.